Coventina.

Coventina

We find Coventina at a single site, Brocolita (now Carrawburgh), in Northern England along Hadrian’s wall. She is a Goddess connected to waters, springs, towns and meeting places, heads and cosmic wheels, and may have even been worshipped in Spain and France. We will start by looking at the meaning of Coventina’s name, discussing Her temple and offerings, looking at what the offerings may tell us about Her, and lastly, discussing Her possible worship abroad and then finishing off with our interpretation of this information.

Etymology

Palacios (2017) proposes several possibilities for the etymology of Conventina, including non-Celtic etymology, most of which they later dismiss. They propose three Celtic etymologies for -vent after defining co- as coming from proto-Celtic kom-, meaning together (Palacios 2017). First *gwent ‘worry, excited’, related to Welsh gwanu. Second Venta ‘field’ which is proposed to become Welsh gwent. Third, proto-Celtic *wentā- ‘place, town’. Palacios goes on to suggest these Celtic etymologies for -vent are unlikely due to unproven semantic changes.

Palacios (2017) then suggests four Latin etymologies for Coventina, although one they discard quickly, leaving three possibilities. The first, convenire ‘to meet with’, ‘to speak to’. Second, conventus ‘meeting, assembly’. And third, vēndĭta ‘market’ and Vulgar Latin venta ‘place of rendezvous for market-people’. They propose that the morphology and semantics make these etymologies possible.

An approach used by Sigroni (2022) ‘combines’ all possible etymologies to build a ‘three-dimensional’ picture of the God in question, which is a beneficial approach when there is no agreed-upon etymology. If we build a ‘third-dimensional’ picture of Coventina, we could see Coventina as a Goddess of place, of coming together to exchange goods and ideas, a Goddess of towns and markets, and all which that entails.

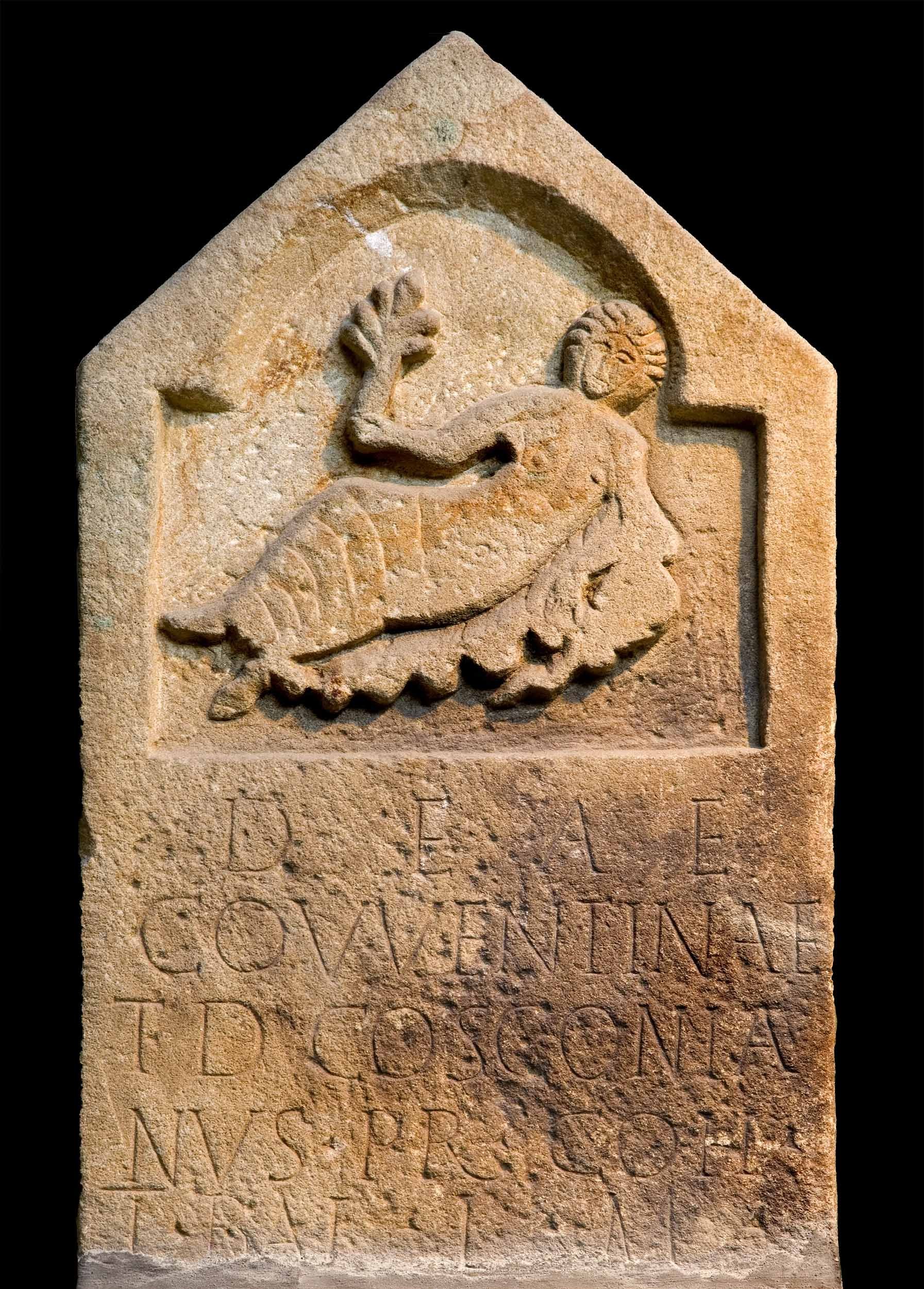

Coventina depicted on RIB 1543, she is often described as lounging on a water-lily leaf (Aldhouse-Green 2018, p. 117), but Coventina may be laying on the water and the lapping waves of a stream may appear like a leaf. The flower Coventina holds may be that of the wild musk flower which grows in Her well during the summer (Tomlin 2018, p. 329). Image from English Heritage (English Heritage Link.)

Coventina’s temple and offerings

A typical Romano-Celtic temple has a cella, an inner roofed area to the temple, usually only accessible by the priest/s. The cella is often surrounded by a portico or gallery, where other cult items are displayed and are open for non-priests (Aldhouse-Green 2018 p. 80). However, Coventina’s temple was completely open-air and the cella was replaced by the spring-well with the outer wall marking the sacred space of the temple (Aldhouse-Green 2018, p. 116). It is also possibly one of, if not the only, Romano-Celtic temple in Britain to have a west-facing door (Irby-Massie 1999, p. 156).

There is a wide variety of offerings left within the waters at Coventina’s temple, one of the most interesting being brooches which take the form of ‘discs, wheels or solar symbols’ (Irby-Massie 1999, p. 157) and skulls/heads (discussed further below). Of the wheels, Irby-Massie suggests “these wheels might connect Coventina to the solar wheel god, vanquisher of dark forces, possibly as his consort. The well itself probably linked Coventina to the underworld, a goddess of death, a vanquisher of death. The evidence points to a predominantly military cult: soldiers worshipped the goddess, and wheel votives imply a vanquishing deity.“

The wheel, most often seen as a cosmic symbol, is said to represent the cycles of life and death, light and darkness, order and chaos. The wheel is often found on Jupiter columns and altars to Jupiter, suggesting that the ‘king of the heavens’ symbol is that of the wheel (Aldhouse-Green 2018, p. 100-103). If perhaps Irby-Massie is correct, and Coventina was associated in some way with the Brittonic God of the heavens or the great cosmic cycles that the Gods tend to.

Another collection of interest is the soles of shoes, which have been found in other sites with a funerary context (Allason-Jones p. 118). Perhaps the dead needed good shoes for their journey, but why deposit them in Coventina’s waters unless She was connected to the dead in some way? The west-facing door hints at a possible association with death or the movement of souls. In Roman and British religious understandings, the dead would travel to the west to reside on a blessed isle.

Mythically, Coventina may have welcomed souls within Her watery domain and transported them or held them until they were ready for their journey west. Perhaps Coventina looks through her west-facing door, out to the isle of the dead and defeats death; just as the sun setting in the west is swallowed by the ocean, Coventina may have been seen to swallow the dead and allowed them to be reborn from Her watery depths.

The triplicate image could represent Coventina in a triplicate form, or Coventina flanked by two attendants, another possibility is that the triple image comes from the shrine of the nymphs just south of Covetina’s Well and was deposited within the well when both sites were shut down (Feris 2021 p. 60). Image from Twitter (Twitter link).

Cult of the head

Skulls are found within at least 10 wells from the West Country to Hadrian’s Wall, including Coventina’s well (Hutton 2013, p. 267), one deposit of coins was given within the cranium of an individual (Aldhouse-Green 2014, p. 206). In addition to the cranium, there are three small bronze masks, the head of a male statue, a pot with a face on the handle, and faces on one of the altars (Allason-Jones 1996, p. 118). What is the significance of heads and skulls within Brittonic religion? A common interpretation of the symbolism of heads in Celtic religion is that they represent the ‘seat of the soul’ and that by embalming these heads, the soul cannot reincarnate or transmigrate into another body to harm them (Ross 1974, p. 161-162)

Furthering this, Siculus says of the Gauls:

“When their enemies fall they cut off their heads and fasten them about the necks of their horses; …and these first-fruits of battle they fasten by nails upon their houses, just as men do, in certain kinds of hunting, with the heads of wild beasts they have mastered. The heads of their most distinguished enemies they embalm in cedar oil and carefully preserve in a chest, and these they exhibit to strangers, gravely maintaining that in exchange for this head some one of their ancestors, or their father, or the man himself, refused the offer of a great sum of money. And some men among them, we are told, boast that they have not accepted an equal weight of gold for the head they show…” - Siculus, Library of History, 5.29

Considering mythical understandings of other cultures can give us an alternative view, one more closely linked to wisdom and memory than the soul. Mimir's head is a common example of heads being linked to wisdom rather than the soul. Mimir guards His well, the waters from which grant wisdom when drinking from it (Dodge 2020). Odin decapitates Mimir and brings His head along as an advisor. Despite Mimir being decapitated, He can still provide wisdom to Odin because He is speaking from memory (Dodge 2020). Both at Mimir’s well, and other wells of wisdom, they commonly have a vessel used specifically for drinking from the waters (Dodge 2020). In the picture below, we see a vessel that may have been associated with this ritual usage.

Furthering the idea of heads as sources of wisdom and memory, Aldhouse-Green (2018, p. 139-141) suggests that many of the heads found in Britain could have been used as ‘oracle stones’. The open mouths of the heads hinting at divine knowledge being spoken to those who would listen. The stone heads mentioned were found in hidden locations, one in the ground and another hidden within a garden, much like the heads deposited into Coventina’s well. The very location of the heads implies secrecy and further links the heads with ideas of wisdom and sacred memory. Indeed, in many Irish and Welsh texts, waters are often seen as ‘confluences of wisdom’ (MacLeod 2006), and this could also be true for the waters at Coventina’s temple.

Beyond the head as a font of wisdom, in the Mabinogion, the beheaded Brân is a protective talisman against invaders and disease who is carried and buried to grant this protection (Koch 2006, p. 236-8). Indeed, there was even a fort in Norfolk named Branodūnum, which may be named after Brân (or the other way around) (Koch 2006, p. 237).

The replicated face pot from Coventina’s well may have been used in ritual, similar to how vessels were used in myth to collect and pour waters of wisdom. Replica face pot from Potted History (Potted History Link).

Coventina abroad

Simón (2005) suggests a linkage between Coventina and the Celtiberian Goddess Cohvetena in Galicia and possibly at Narbonne as well (Koch 2006, p. 494-495). As the spellings are different even compared to the fluid spelling in Britain, there is a possibility the goddesses in Galicia and Narbonne are not Coventina but someone else (Allason-Jones 1996, p. 111-112).

The importance of Coventina as more than a local Goddess is strengthened by the fact that She is the only non-Capitoline Goddess (Juno and Minerva) in Britain to be called both sancta and augusta (Allason-Jones 1996, p. 112).

Interpretatio Britanna

Through Her etymology, we can know Coventina as a Goddess of meeting, place and space, of trade and sharing of ideas. Combining this with Her connection to heads and waters, She is a Goddess who grants us sacred memories and wisdom, who enables connection with others and ourselves. With Her linkage to wheels, shoes and the west, we could propose a connection in some way with the greater cosmic cycles. Perhaps She ferries souls, or Her waters are the ‘pick up’ location for souls, maybe the dead dwell in Her waters, imparting it with their memories and wisdom, for it to be passed onto worshippers by Coventina later. But with Her wide-ranging aspects, we could describe Her as an ‘all-rounder’ deity (Aldhouse-Green 2004, p. 208) who aids Her worshippers in any way. As modern Brittonic and Brythonic polytheists, we can call on Coventina for aid in connecting to people and place, for wisdom and memory, and likely for anything else one would call on a Goddess of waters on, including healing.

Prayer to Coventina

Rise O Western Queen,

Accompanied by your enduring attendants,

And yourself.

Pour out wisdom from your cups,

Break the drought we suffer under,

Let us taste the sweet streams,

And be divinely supplied.

We raise our cups to your Western Throne!

We pour out praise from our mouths,

Having tasted the sweet streams,

Our praise is divinely supplied.

You have given so that we may give.

Praise to you, Coventina, three and one,

Western Queen and source of wisdom.

Inscriptions

“To the goddess Conventina Bellicus set this up, willingly and deservedly fulfilling his vow.” (RIB 1522)

“To the goddess Convetina Mausaeus, optio of the First Cohort of Frixiavones, paid his vow.” (RIB 1523)

“To the goddess Coventina for the First Cohort of Cubernians Aurelius Campester joyously set up his votive offering. “ (RIB 1524)

“To the goddess Coventina Aurelius Crotus, a German, (fulfilled his vow).” (RIB 1525)

“To the goddess-nymph Coventina Maduhus, a German, set this up for himself and his family, willingly and deservedly fulfilling his vow.” (RIB 1526)

“To the Nymph Coventina …]tianus, decurion, … deservedly [fulfilled his vow].” (RIB 1527)

“To the goddess Coventina Vinomathus willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.” (RIB 1528)

“To the goddess Coventina P[…]anus, soldier of the … Cohort, willingly paid his vow and set this up.” (RIB 1529)

“Gabinius Saturninus (son) of Felix.” (RIB 1530) [dedication on an incense burner]

“For Covetina Augusta Saturninus Gabinius made this votive offering with his own hands.” (RIB 1531)

“To the goddess Covetina I, Crotus, willingly fulfilled my vow for my welfare.” (RIB 1532)

“To the holy goddess Covontina Vincentius for his own welfare as a vow gladly, willingly, and deservedly dedicated this.” (RIB 1533)

“To the goddess Covventina Titus D(…) Cosconianus, prefect of the First Cohort of Batavians, willingly and deservedly (fulfilled his vow).” (RIB 1534)

“To Covventina Aelius Tertius, prefect of the First Cohort of Batavians, willingly and deservedly fulfilled his vow.” (RIB 1535)

Bibliography

Aldhouse-Green, M., 2004. Gallo-British deities and their shrines. A Companion to Roman Britain, pp.193-219.

Aldhouse-Green, M.J. (2018). Sacred Britannia: the gods and rituals of Roman Britain. London; New York: Thames & Hudson.

Allason-Jones, L., 1996. Coventina's Well. The Concept of the Goddess, pp.107-119.

Diodorus Siculus. Library of History (Books III – VIII), trans. C. H. Oldfather. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1935. Accessed: https://exploringcelticciv.web.unc.edu/diodorus-siculus-library-of-history/.

Dodge, E.J., 2020. ORPHEUS, ODIN, AND THE INDO-EUROPEAN UNDERWORLD: A RESPONSE TO BRUCE LINCOLN’S ARTICLE “WATERS OF MEMORY, WATERS OF FORGETFULNESS” (Doctoral dissertation, University of Houston).

Ferris, I. (2021). Visions of the Roman North: Art and Identity in Northern Roman Britain. Oxford Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Hutton, R. (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Irby-Massie, G.L. (1999). Military religion in Roman Britain. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Koch, J.T. (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. Oxford: Abc-Clio.

MacLeod, S.P., 2006, January. A Confluence of Wisdom: The Symbolism of Wells, Whirlpools, Waterfalls and Rivers in Early Celtic Sources. In Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium (pp. 337-355). Dept. of Celtic Languages and Literatures, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University.

Palacios F F., Chapter 9 ‘The theonym *Conventina’ in R Haeussler and King, A. (2017). Celtic religions in the Roman period: personal, local, and global. Aberystwyth, Ceredigion, Wales; Havertown, Pa: Celtic Studies Publications.

RIB 1522, Altar dedicated to Conventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1522.

RIB 1523, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1523.

RIB 1524, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1524.

RIB 1525, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1525.

RIB 1526, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1526.

RIB 1527, Dedication to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1527.

RIB 1528, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1528.

RIB 1529, Altar dedicated to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1529.

RIB 1530, Dedication to Coventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1530.

RIB 1531, Dedication to Coventina Augusta, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1531.

RIB 1532, Altar dedicated to Covetina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1532.

RIB 1533, Altar dedicated to Covontina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1533.

RIB 1534, Dedication to Covventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1534.

RIB 1535, Altar dedicated to Covventina, Roman Inscriptions of Britain, https://romaninscriptionsofbritain.org/inscriptions/1535.

Ross, Anne (1974). Pagan Celtic Britain: Studies in iconography and tradition. London, UK: Sphere Books Ltd. pp. 161–162.

Sigroni, C. (2022). (Apollo) Grannus: What’s in a Name? [online]. Available at: https://sigroni.wordpress.com/2022/04/04/apollo-grannus-whats-in-a-name/ [Accessed 12 Apr. 2022].

Simón, F.M., 2005. Religion and religious practices of the ancient Celts of the Iberian Peninsula. E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies, 6(1), p.6.

Tomlin, R.S.O. (2018). Britannia Romana Roman inscriptions and Roman Britain. Oxford Philadelphia Oxbow Books.